SphereCam for Marine Monitoring: 2016 REU

Vaquita marina is a critically-endangered porpoise endemic to the northern gulf of California, between the fishing villages of San Felipe and El Golfo de Santa Clara. First discovered in 1958, the population has rapidly declined over the last few decades due to poaching and bycatch in gillnets used by local fisheries. As of mid-2016, it is estimated that there are less than 60 individuals left in the wild, and due to their secretive nature, the only pictures that exist are either from far away on the surface or dead in nets. Many conservation efforts are underway in Mexico, including a recent ban on gillnet use and increased enforcement to deter poaching. Local support is key to these efforts; getting pictures and video of the vaquita in its natural habitat would help make the vaquita a point of pride for the local population.

Camera traps are devices that allow biologists and ecologists to get pictures and video of animals that are rare and reclusive. Without camera traps, a scientist would spend days to weeks hiding in a blind with a camera hoping for a chance to get a picture. With a camera trap, the scientists can instead place one (or many!) camera traps that will trigger based on the presence of the target animal, and capture data for weeks at a time. A scientist can use camera traps to monitor more territory and for longer periods of time. Most camera traps are designed for terrestrial use and trigger based on motion, heat, or vibration. Our SphereCam is a new type of camera trap, specially designed to capture photos, video, and audio of the vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus) in a marine environment.

System Requirements

For a camera trap to be most effective, it needs to be left out in the Vaquita habitat for a significant amount of time. The Vaquita is not only rare but more solitary than other marine mammals. More deployment time means more opportunities for a Vaquita sighting. Taking into consideration the location and the ability to service the camera a week of operation is the goal for the Spherecam.

Cameras take an enormous amount of energy to run, especially the six GoPro cameras mounted inside the Spherecam. Turning the cameras on only when there is a good chance of getting a picture is key to saving battery power, and lengthening deployment time. While there are not recordings available to us at this time, there are recordings of the Vaquita, and we know at what frequency it echolocates, and we can record and trigger of these sounds.

Everything, including a battery, has to be small enough to fit inside a commercially available waterproof enclosure. It also has to be able to manage the heat of operating in an enclosed space, where the water outside is too warm to offer much cooling.

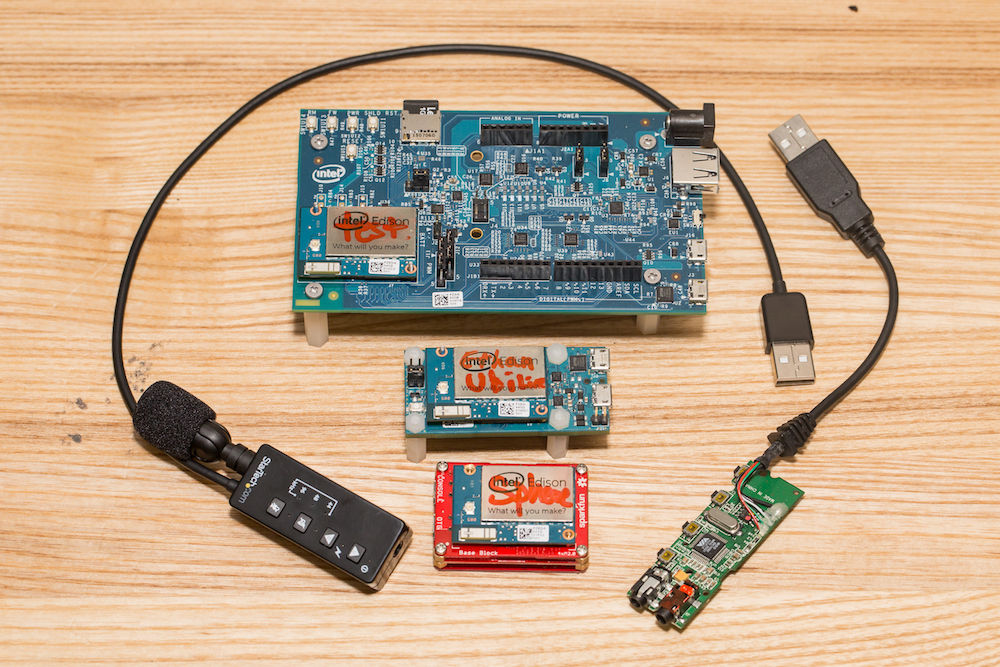

New Computer System

This summer a new computer system was selected for the Spherecam, the Intel Edison compute module. The Intel Edison is ideal because of its small size, low power use, and dual core processor. Since the Edison was new, a significant amount of work went into the integrating of the Edison into the system and the creation of a stable and reliable development environment.

The Edison runs a Yocto Linux operation system which is very powerful and lightweight but also has a very steep learning curve. Programs for the Edison also have to be cross compiled, which means that although we can program on a normal computer, we have to compile our programs either on the Edison itself (slow!) or in a special way on a normal computer. A non-trivial amount of time was spent learning, setting up, and documenting the process of Yocto and cross-compiling programs.

While this is not the most exciting part of the project, it is an import part of any computer engineering project and creates a way for future development to happen much more rapidly. Documenting the process for future students is the most important part of this process.

Triggering

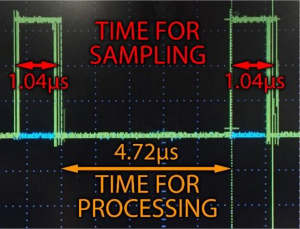

Triggering was the biggest technical challenge this summer. The Vaquita uses echolocation clicks that are at around 139kHz (For reference Humans can hear from 20Hz - 20kHz). The Nyquist theorem also stipulates that to record an analog signal accurately, like a sound, digitally we need to sample at least twice the rate of the sound we want to record. Because of this, we need to sample the audio signal at about 300kHz to be able to detect the 139kHz tone, or in other words, the computer has to read the microphone signal and record a value 300,000 times per second.

How long does it the computer take to read each value? How much time does that leave between samples to do other things like detecting the Vaquita and storing the audio to a file? Each sample is two bytes in size creating a data stream of 600,000 bytes per second, can the bus handle that throughput? These are the big engineering questions when tackling the problem of recording ultrasonic sound. While a few other attempts have been made, nobody we know of has come up with a good solution for low power embedded computers.

Attempts To Sample at Required Speed

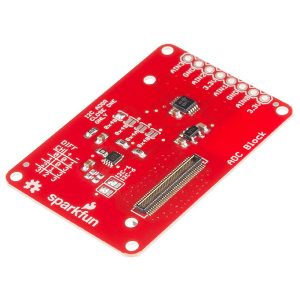

Edison ADC breakout: Made by Sparkfun this board provides a €œbuilt-in€ ability for the Edison to take readings from a microphone using an Analog to Digital Converter (ADC). Because Linux is not a real-time system and there is an inherent latency with accessing the ports on the Edison this was able to sample at a maximum rate of about 9,000 Hz. Not good enough!

Edison MCU: The Edison has a built in real time microcontroller that could theoretically control an external ADC, but the protocol that most high-speed ADCs use is not currently supported (SPI). The bandwidth to transfer data from the MCU to the Edison is also not able to support 600kBps.

Edison MCU: The Edison has a built in real time microcontroller that could theoretically control an external ADC, but the protocol that most high-speed ADCs use is not currently supported (SPI). The bandwidth to transfer data from the MCU to the Edison is also not able to support 600kBps.

Teensy3.2 / ATMega32U4: Realizing that a real-time microcontroller talking to an external ADC is the only realistic option we moved to attempting either a 32-bit ARM Cortex M4 or a USB enabled ATmega processor. Both produced good results but topped out at about 150,000 samples per second. The transfer of the data from the microcontroller was also very unstable despite both supporting USB.

Teensy3.2 / ATMega32U4: Realizing that a real-time microcontroller talking to an external ADC is the only realistic option we moved to attempting either a 32-bit ARM Cortex M4 or a USB enabled ATmega processor. Both produced good results but topped out at about 150,000 samples per second. The transfer of the data from the microcontroller was also very unstable despite both supporting USB.

Sound Card: The final and most stable case was to use a consumer USB sound card. The USB protocols describe a sound device, meaning that a device that meets those specifications can work without drivers. High-quality consumer cards are capable of sampling at up to 192,000Hz. Using a USB-Audio device also allows us to use the large library of open source libraries available for dealing with audio data.

Sound Card: The final and most stable case was to use a consumer USB sound card. The USB protocols describe a sound device, meaning that a device that meets those specifications can work without drivers. High-quality consumer cards are capable of sampling at up to 192,000Hz. Using a USB-Audio device also allows us to use the large library of open source libraries available for dealing with audio data.

Although the external ADC and microcontroller did not work, it is most likely due to failures on our part. Sampling at such high speeds is not easy, but progress was being achieved. Given more time digging through datasheets and a more thorough understanding of the low-level USB protocols, it is certainly achievable. Given the timeframe of the project, the USB-soundcard was selected as the solution to meet our needs in the timeframe given. Another part of this project working on in parallel was a module to shift the high frequency of a vaquita click down into a lower frequency range to make recording easier. This module combined with the moderately fast speeds of a USB sound card create a complete system capable of achieving our original goals.

Software Design

Now that the signal is in in the Edison, the software design was the next problem. Designing the software was much more straightforward than the hardware. Several open source libraries were used to include portaudio, libsndfile, and FFTW. Portaudio gives an easier programming interface to the Linux ALSA audio framework, as well as providing a thread-safe non-locking circular buffer. Libsndfile provides a sound file interface that allows the Edison to write data to an audio file without worrying about the endianness of the data or the specifics of audio file formatting. Lastly, FFTW is an extremely optimized library that can perform Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) on real data, for detecting the amplitude of the audio at specific tones. In addition to FFTW we implemented a tone detection module using the Goertzel algorithm, which can detect single tones much faster than an FFT in theory. Moving forward some real tests to compare the two techniques need to be performed to see which one is faster and more accurate in practice. All of this together creates the software currently running on the Edison, with data acquisition and storage happening on one core and tone detection taking place on the other core.

Field Testing

Early in the summer, we attempted to deploy the SphereCam in the Vaquita Refuge to get a baseline on the level of ambient noise in the same frequency range as the vaquita’s echolocation clicks. However, bad weather waylaid our fieldwork plans.

Ethan makes some repairs in the field

In early September, we deployed the SphereCam in the Vaquita Refuge. It will remain in the refuge until late September, at which point we will return to swap the batteries, grab the data, and clean the domes of biofouling. Check back later for more updates on what the SphereCam sees!