Mangrove Monitoring REU Trip - July 2018

Mangroves are a coastal ecosystem that provides extremely valuable services: they sequester 2-4 times more carbon than tropical rainforests, protect coastlines from storm systems, and provide excellent fisheries. Unfortunately, mangroves are at risk due to human encroachment and the government lacks adequate information to provide effective enforcement to protect these sanctuaries.

Engineers for Exploration has been working with Aburto Lab at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography to monitor mangroves by using drones, advanced imaging sensors, and machine learning. The goal is to provide a large-scale classification of the mangroves ecological characteristics and ultimately use that data to drive conservation efforts in Baja California, Mexico. On our most recent trip to collect more data, we learned how complex and interesting these ecosystems are while analyzing our current field techniques.

Left to right: Brian Rush, Savannah Longoria, Eric Lo, Dillon Hicks, Kathy Qi, Catherine Lee

Drone Work

Our Engineers for Exploration team (Eric Lo, Savannah Longoria, Kathy Qi, Dillon Hicks, Brian Rush and Catherine Lee) went to Baja Sur California with the Aburto Lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) from July 11-18 to collect aerial and on-the-ground data to document several mangrove sites. The primary purpose of this expedition was to improve and implement new data acquisition techniques from previous expeditions in May 2018 and July 2017, in order to calculate mangrove biomass and classify species effectively and train new people to gather data. This will allow us to support and improve the other stages of our project such as machine learning techniques and data analysis.

On this trip, we made specific improvements to our data collection process. In the past we flew the drone at 50m and 120m. This time added some additional perimeter surveys at 10m. This data allows us to look at the mangrove species in high resolution, which we believe is necessary to perform mangrove species identification. The higher resolution data allows us to improve training data for our algorithms and better understand the resolution required to perform classification.

In addition to this, we were able to create orthomosaics of our data in the field. This allowed us to ensure the data the drone is collecting is adequate enough for our research, and advise the drone pilot to collect more data if needed.

In previous trips, the exposure and color varies in the images we collected due to changes in sunlight throughout the day. By including a color calibration photo at the end of each flight, we standardized these different lightings and created a consistent exposure.

On this trip I learned that drones provide a new opportunity for researchers to gain insight on sites that would otherwise be inaccessible. When we went in the field we learned that mangroves are dense and really hard to navigate. However, using drone imagery to classify mangrove species and calculate biomass is also its own unique challenge. There is essentially always improvements to be made, and always something new to learn about taking our technology out in the field. We hope for our next expedition we are able to collect ground control points. These ground control points will allow us to have a reference when aligning different layers and establish points with known elevations.

Bahia Magdalena

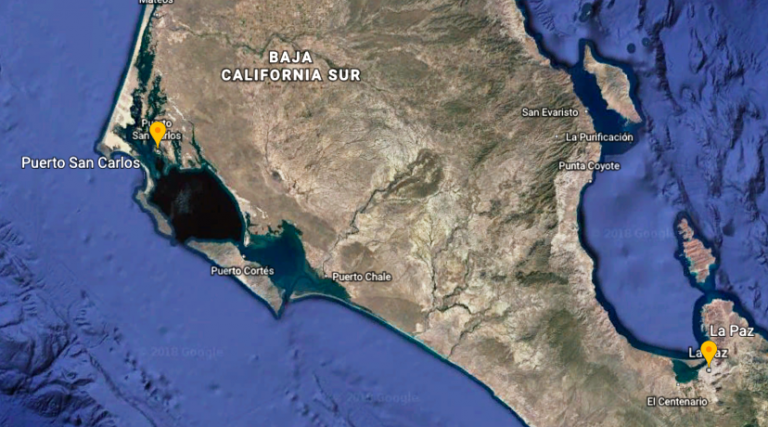

For the next part of our trip, we traveled to Puerto San Carlos in Bahia Magdalena with a much smaller team than we started out with. The main purpose for this segment was to meet and train with CONANP, an organization dedicated to conservation in the Gulf of California. In addition, our team would also be surveying past sites through on the ground measurements and drone work with improved methodologies developed on the last trip. I learned that mangrove sites could vary significantly by location even in La Paz, so I was interested in seeing how the forests grew in a different region.

After a long drive and a night’s rest at the hotel, our team went to work at one of the larger sites that we had previously flown at. Almost immediately, we noticed that the geography of this region was distinct from La Paz as the terrain was considerably more flat. The difference showed its effect in the many of the black mangrove leaves, _Avicennia germinans, _as they exhibited none or little salt crystals compared to the trees from our previous sites. Since there was almost no change in elevation throughout the forest expanse, the smoother transition of salinity seemed to cause more mixing of the three species. This interesting observation can be seen with our aerial data and is an example of the essential role fieldwork has in distinguishing the fascinating patterns and anomalies of wetland ecosystems. We continued to conduct aerial and ground surveys for a couple more regions, collecting more data to analyze and measure in the lab.

A main goal for this project is to have local people to fly drones over mangrove forests and provide us the aerial imagery to be constructed into models that will provide us important information for research. During the trip, we met with CONANP at a site to teach them the basics of aerial surveys with the drone and began establishing a better relationship between our groups. This collaboration could provide future connections to increase our potential for collecting data efficiently and promote better management efforts of mangroves together. From this experience, I learned an important cultural lesson that sometimes research not only requires the knowledge and tools for acquiring the data we need, but also establishing connections with people to expand our outreach.