E4E Winter 2020 Projects

We’ve got some exciting new projects for Winter 2020, in addition to our currently running projects. To recap, our projects range from applications to determine population counts for endangered and rare animals, to creating and visualizing data to uncover ecological and archaeological discoveries (e.g. understanding environmental impacts on coral reefs and mapping Maya structures). We are centered around student-led teams who tackle the design process from beginning to end, from planning and prototyping various designs, culminating in deploying the system in the field alongside scientists and explorers. Below are quick summaries of the projects we are actively recruiting for. Follow the links to each project to learn more about the projects and how to get involved!

Automated Acoustic Species Identification

Rainforest Environment

Biologists increasingly deploy autonomous audio recorders that are placed in natural habitats and record audio at fixed intervals (e.g. 1 minute every 5 minutes) for weeks or months. These recordings can be used to detect individual species that have unique vocalizations including birds, amphibians, bats and certain mammals such as primates. They can also detect human threats such as gunshots, chain saws, engines. For large surveys biologists can deploy 30-100 recorders simultaneously resulting in a huge volume of data. The goal of this project is to build a machine learning pipeline that can handle this kind of data and automatically detect and extract vocalizations of species of interest. The following points would need to be addressed: general data management; efficient labeling of vocalizations to be used for model training; development of models to classify sound recordings; and a pipeline to extract recordings and perform quality control. Our collaborators at the San Diego Zoo currently have data from about 80 recorders deployed in the Peruvian Amazon with close to 1 year of total recording time and we have species experts that can help with manual labeling. However, one of the first challenges is how to efficiently create training data for a large number of species from hours or days of unlabeled recordings, probably involving some unsupervised clustering.

Animal Action Recognition from Images and Videos

Female Burrowing Owl

The San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research has a number of projects where the activities (behaviors) of animals are determined manually from videos and images captured in the field by camera traps or surveillance cameras. For example, researchers studying burrowing owls not only keep track of the presence and number of owls and their predators in camera trap images but also record mating and predation events caught in those images. Behavior or action recognition using machine learning is a growing field with demonstrated success in a number of applications. We seek to investigate the potential of action recognition techniques in automating the process of labeling the behaviors of animals in our field images and videos. For the burrowing owl study in particular we have a very large repository of hand-labeled images as a starting point.

Autonomous Trap Monitoring System

Deployed feral animal trap

Biologist use a wide range of live traps to capture animals. These can range from small box traps for rodents, to large cages or snares for carnivores. A trapping grid can consist of 10 to several 100 traps spaced from a few meters to a few miles apart. Monitoring these traps to quickly process and release the animal is crucial. Many species suffer stress or even get injured when left in traps for too long. To date, most traps are monitored visually by field technicians. This is labor intensive and animals can spend a long time in a trap. If biologists had a prior knowledge of which traps had caught animals, they could get to those traps first. While trap transmitters that send a signal when a trap has been activated already exist, they are either based on a radio transmitter with limited range or use a satellite transmitter that is expensive and requires a subscription. All of these factors limit the use of trap transmitters for most studies. This project will design a modification to existing traps that will allow scientists to remotely monitor the trap using existing wireless infrastructure.

Maya VR

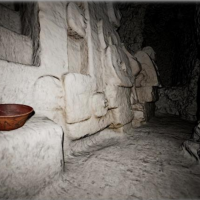

Structure M7-1 in El Zotz, Guatemala visualized using Unreal Engine

Traditional methods of documenting findings in archaeology has been through illustrations and photographs, but archeologist now digitally

archive these locations using LiDAR and Photogrammetry due to their increased accuracy. This method of creating environments has become more popular in recent years, thus we have a lot of raw data in the form of point clouds and photographs to experiment with in order to achieve the most accurate result. The goal of the project is to explore digital methods for documenting, visualizing, and sharing archeological finds to then prepare as an Oculus Quest museum exhibition for Guatemala City.